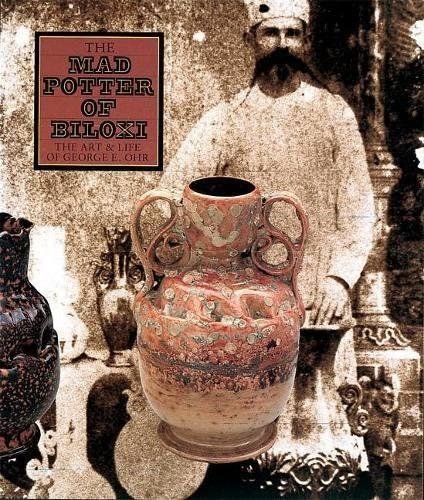

THE MAD POTTER OF BILOXI

BILOXI, MISSISSIPPI -- Riding the train south, then farther south, tourists came to Biloxi for sunshine and surf. But at the turn of the 20th century, the Gulf Coast town boasted a new tourist attraction, one based on genius. Or madness, depending. . .

At the base of a five-story pagoda, the sign read BILOXI ART POTTERY. Below it were hand-lettered signs. “Get a Biloxi Souvenir, Before the Potter Dies, or Gets a Reputation.” “Unequaled unrivaled—undisputed— GREATEST ART POTTER ON THE EARTH.”

Stepping inside, a tourist found a studio overflowing with pots, but not your garden variety. These pots had rims crumpled like burlap bags, pitchers twisted, vases warped as if melted in the kiln. And colors! Blood reds, gunmetal grays; olive greens splattered across bright oranges. The entire studio seemed like some mad potter’s hallucination, and standing in the middle was the mad potter himself.

With huge arms folded across his dirty apron, George Ohr looked more blacksmith than potter. But there was something in Ohr’s eyes—piercing and wild. If the pots and the man’s appearance did not prove lunacy, his prices did. He wanted $25—about $700 today—for a crumpled pot. “No two alike,” he boasted, but each looked as weird as the next. No wonder Ohr's pots collected dust. As his work went unnoticed, unsold, he said, “I have a notion that I am a mistake." Yet he predicted, “When I am gone, my work will be praised, honored, and cherished. It will come.”

Today Biloxi hosts another tourist attraction, an entire museum devoted to the mad pottery of George Ohr. Though "artist-ahead-of-his-time stories" are cliché, George Ohr staged the art world’s most remarkable comeback. For although his work is now in New York’s Metropolitan and other major museums, until the 1970s, the only place to see an Ohr pot was in a garage behind a Biloxi auto shop—in a crate.

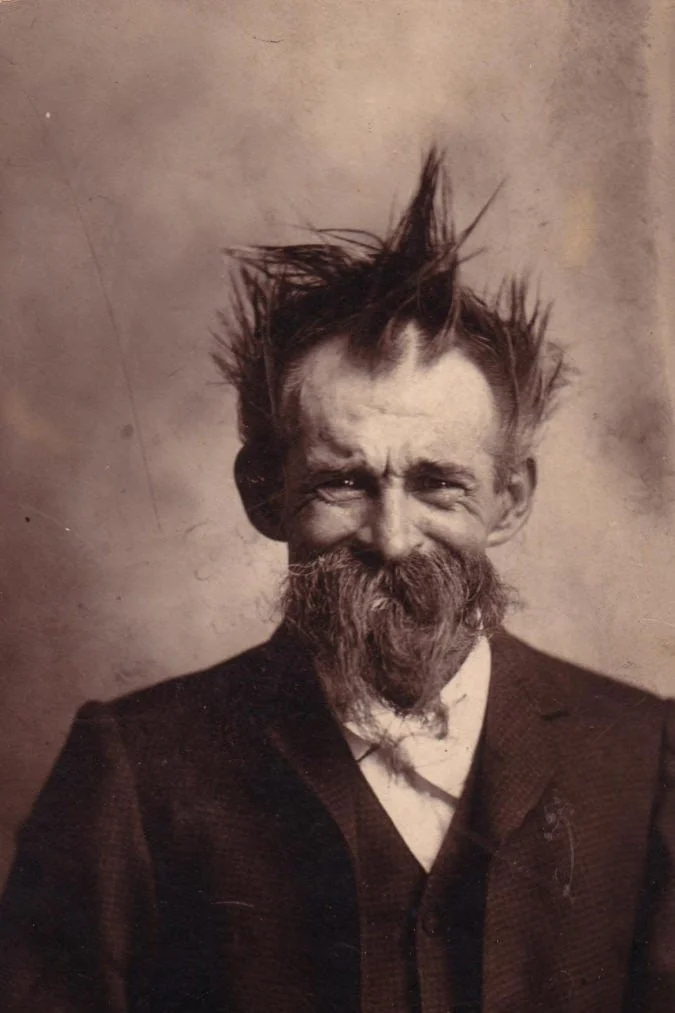

George Ohr made his living shaping clay but he also shaped himself and his image. He called his pots his "mud babies." He called his studio the Pot-Ohr-E. In a local photography studio, he twisted his 18-inch mustache and face to produce some of the wackiest portraits ever taken. But when he "found the potter’s wheel," he said, "I felt it all over like a wild duck in water."

During the 1890s, as Cézanne was breaking up the plane of the painter’s canvas, Ohr was shattering the conventions of ceramics. He made pitchers resembling yawning mouths. He threw multitiered vases with serpentine handles. He shaped bowls into symmetrical forms, then crumpled them, thumbing his nose at the art world. And fired his works into kaleidoscopic colors that would later be called fauve—for the “wild” hues of Matisse and other Fauvists.

Locals considered Ohr certifiably insane. Yet he kept at it, his works getting wilder and wilder. Finally, in 1909, claiming he hadn’t sold one of his "mud babies" in 25 years, Ohr closed his shop. Though just 52, he never threw another pot. He let his beard grow. He donned a flowing robe for Biloxi’s Mardi Gras, roaming the streets as Father Time. In his final years, he could be seen racing a motorcycle on the beach, white hair and beard flying.

Still confident that his time would come, Our died of throat cancer in 1918. His pottery remained in the garage of his sons’ auto-repair shop. Every now and then, boys with BB guns would take out pots and use them for target practice. And then. . . .

One warm afternoon in 1968, an antiques dealer from New Jersey was making his annual winter tour of the Gulf Coast. While he was filling up with gas at Ohr Boys Auto Repair in Biloxi. Ohr's son approached. In his slow Mississippi drawl, he asked, “Would y’all like to see some of my daddy’s pottery?” Yeah, sure. . .

Moments later, Ohr's son opened the garage doors to reveal the most amazing collection of pottery in the history of American art. Several pieces were set on tables; the rest filled crates stacked to the ceiling. A few had been cleaned of their greasy film. Catching the sunlight, they sparkled like the day Ohr had given them life.

Today, the same pots scorned a century ago sell for thousands each. And the "Mad Potter of Biloxi" is hailed as “the Picasso of art pottery.” Ohr's resurrection proves that madness, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. But then, he always knew that.

Hadn't one hand-lettered sign outside his studio proclaimed: Magnus opus, nulli secundus/optimus cognito, ergo sum! Translated it read: “A masterpiece, second to none, The best; Therefore, I am!”