WHEN BILLINGS (MT) SAID 'NO' TO HATRED

BILLINGS, MONTANA — In the early 1990s, the hate broke out of hiding. With little fanfare and no Internet, neo-Nazis declared Montana part of a five-state Aryan Homeland. The “purification” began.

First came fliers denouncing Jews. No one in Billings did anything except crumple the creepy papers and hope the hate would go away. Weeks later, red swastikas defaced several Jewish homes. People signed petitions. Church groups met.

Next, a Native-American family got the same treatment — swastikas and the word DEAD scrawled on a house. That’s when the same old sad saga got a different ending.

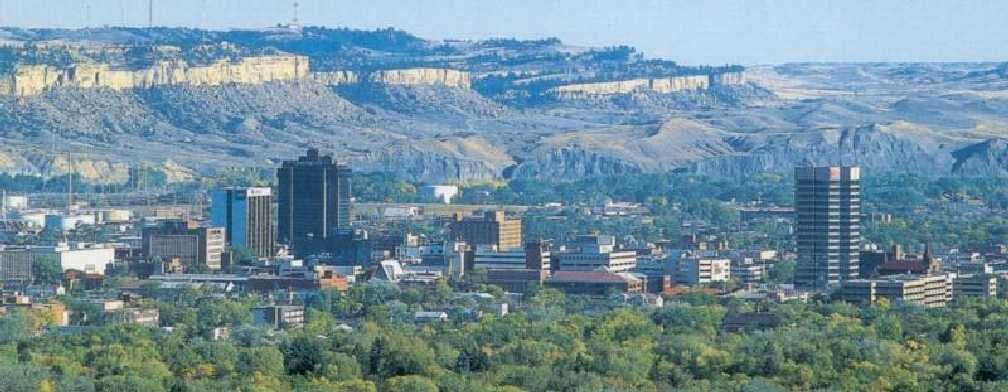

Billings began as a railroad hub on the edge of the Plains. By 1990, it was a city of 80,000. The 50 Jewish families, 500 blacks, and hundreds of Native-Americans had grown accustomed to awkward incidents. Stares. Comments. “You people.” But for the 90 percent of Billings that was white, raw hatred was something new, something ugly, something un-American.

Responding to the swastikas, a newly-formed Human Rights Coalition contacted the local painter’s union. The next day, 30 guys showed up, after work, to completely repaint the house. A hundred people gathered to watch. One house reclaimed, one soul soothed. But the hate wasn’t finished.

Weeks later, Jewish gravestones were toppled. Then racist graffiti defaced the African Methodist Episcopal chapel. One Sunday morning, skinheads entered the church and stood, arms folded, glaring. Members of other churches soon accompanied frightened parishioners to services. The hate moved on.

On December 2, 1993, a brick shattered a boy’s bedroom window that framed a menorah. Five-year-old Isaac Schnitzer and his sister were in another room but their father found the brick. As he sat and wept, a city found its heart.

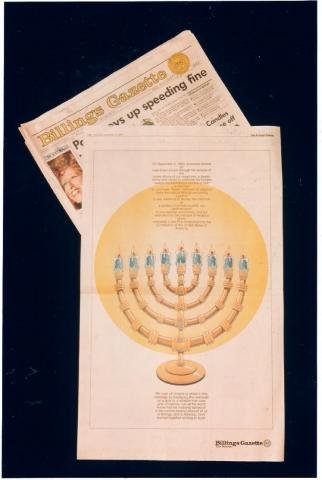

Advised to take down their menorah, Tammie Schnitzer refused. Instead, she started a campaign to put more menorahs in windows. Dozens went up. When the Billings Gazette got word, editor Gary Svee remembered a story of how Denmark, during World War II, resisted the hate.

When Nazis forced Jews to wear yellow stars, hundreds of Danes began wearing their own stars. So on December 7, five days after a brick smashed a menorah, the Gazette printed a full page, tearout menorah. Readers were asked to display it as a symbol of “our dedication under the principle of liberty embodied in the first amendment to the constitution of the United States of America.”

Within a week, paper menorahs graced hundreds of windows in Billings. But the hate fought back. More bricks. Cars outside Jewish homes vandalized. Shots fired. Billings’ response? More menorahs.

Within a week, some 6,000 menorahs were on display in Billings. Then came a candlelight march drawing hundred, and a daytime march (above) with menorahs in hand. The marches’ slogan came from a commercial bulletin board — “NOT IN OUR TOWN!” The menorahs remained in windows for the rest of the year. The hate went back into hiding.

Some downplayed what Billings did. Paper menorahs? “It was the right thing to do,” union organizer Randy Siemers said, “but I feel we’re also expected to do things like this.” When Billings made headlines across America, Siemers and others were surprised. “These are our neighbors,” Siemers said. “If someone throws a brick into your neighbor’s house, in Montana you run out there and try to stop them. Don’t they do that anywhere else in the country?”

In fact, they do. In 1995, PBS aired “Not in Our Town!” The documentary started a movement. The following year a Maine school beset by bullying launched Not in Our School. Other schools followed. Soon Not on Our Campus campaigns started from UC Santa Barbara to Skidmore College in upstate New York.

Today, Not in Our Town works nationwide. NIOT has made documentaries about similar responses to white supremacists in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, in Patchogue, New York, in Northern California, and at the Universities of Mississippi and Indiana.

As in Billings, fighting hatred takes more than heart. NIOT.org offers organizing tips, school lessons, and other strategies for forging diverse groups — churches, police, service groups, town government — into one united front with one determined message.

Responses differ from town to town. Bloomington, Illinois responded with hundreds of umbrellas and shields. Newark, California used angels as symbols. A West Virginia town tried a flash mob. . .

Back in Billings, the hate that all America has lately seen emerged again in 2018. Billings responded by turning swastikas into symbols of solidarity. The battle goes on. “It was just one tiny candle we lit,” editor Gary Svee said, “and it wasn’t much, but it was something.”