WHEN BIGOTRY STRUCK OUT

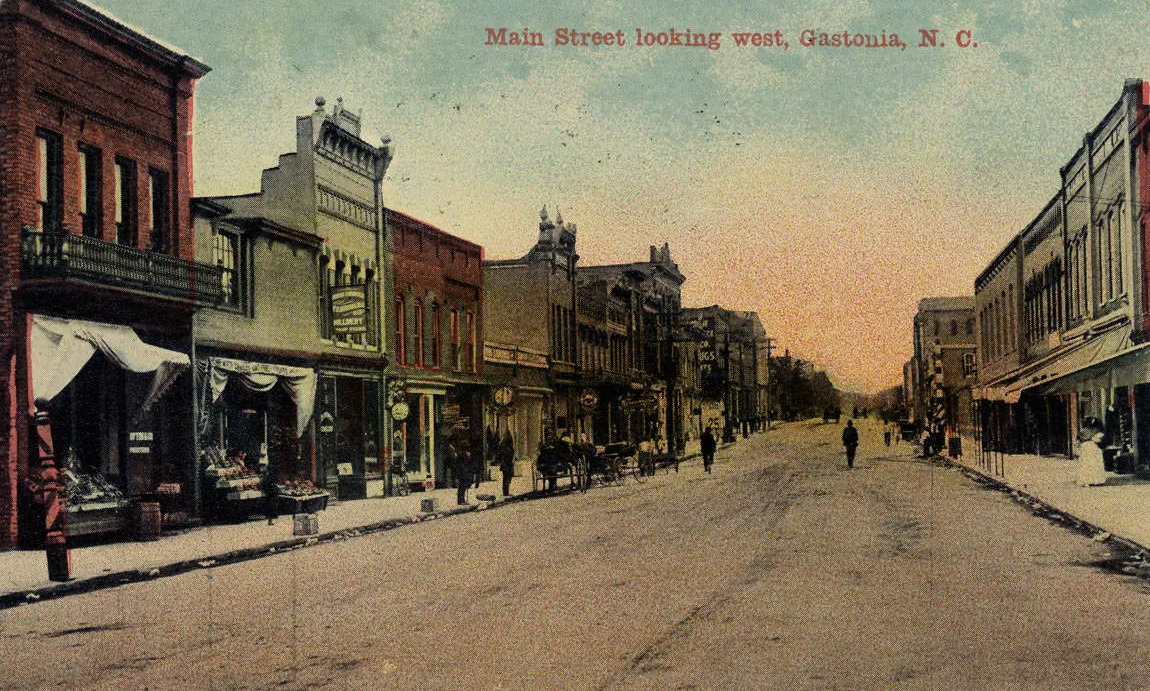

From New England to North Carolina is less than 800 miles. You can catch a morning flight to Charlotte and be in the Piedmont for lunch. But during the Depression, the trip took twenty hours by train. And back then, any damn Yankee arriving in the Jim Crow South soon saw how the rules had changed.

On a warm August morning in 1934, the Springfield American Legion baseball team stood at the train station in the hardscrabble mill town of Gastonia. The team waited for a bus to their hotel. And waited. The kids were eager to play. Just one win stood between them and the national championship in Chicago. Just one win. . .

Minutes later, the bus arrived. But the driver took one look and sped away. Puzzled, players and coaches hefted their bags and walked through the gritty streets to their hotel. There, a sign offered more Southern hospitality: “No niggers or dogs allowed.” The hotel clerk was polite. Those big Irish boys — Kelly and O’Shay — were fine. Likewise the Italians — Malaguti and Lombardi. But the black kid. . .

Teammates called him “Bunny.” He earned the childhood nickname by running everywhere. And in high school, Ernest “Bunny” Taliaferro ran into Springfield’s record books. The Massachusetts industrial city had been home to many athletes, including two future baseball hall-of-famers. Basketball was invented in Springfield. But by 1934, the school track records, the baseball records, and some football records all belonged to Bunny.

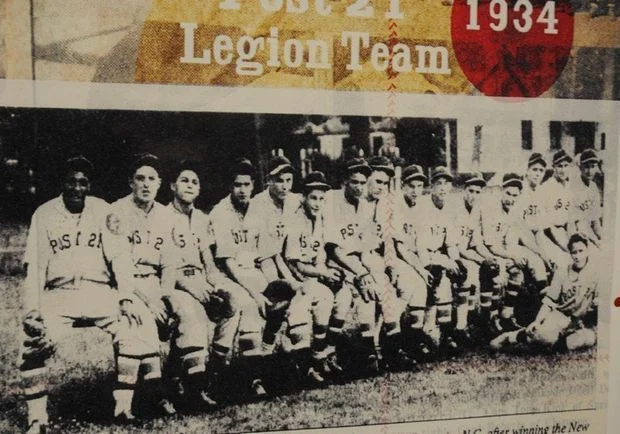

Pitching for American Legion Post 21, Bunny struck out a dozen a game. When not on the mound he roamed centerfield. He stole bases. He led the team to a 12-1 record and pitched three shutouts in the playoffs that sent the team South -- where the rules changed.

With a practice that afternoon, the disgruntled team left their bags at the hotel and walked toward the field. Team captain Tony King was startled to see two black men jump off the sidewalk as he approached. "They couldn't pass me on the sidewalk because they were black, and I was white,” King remembered. “I never forgot that."

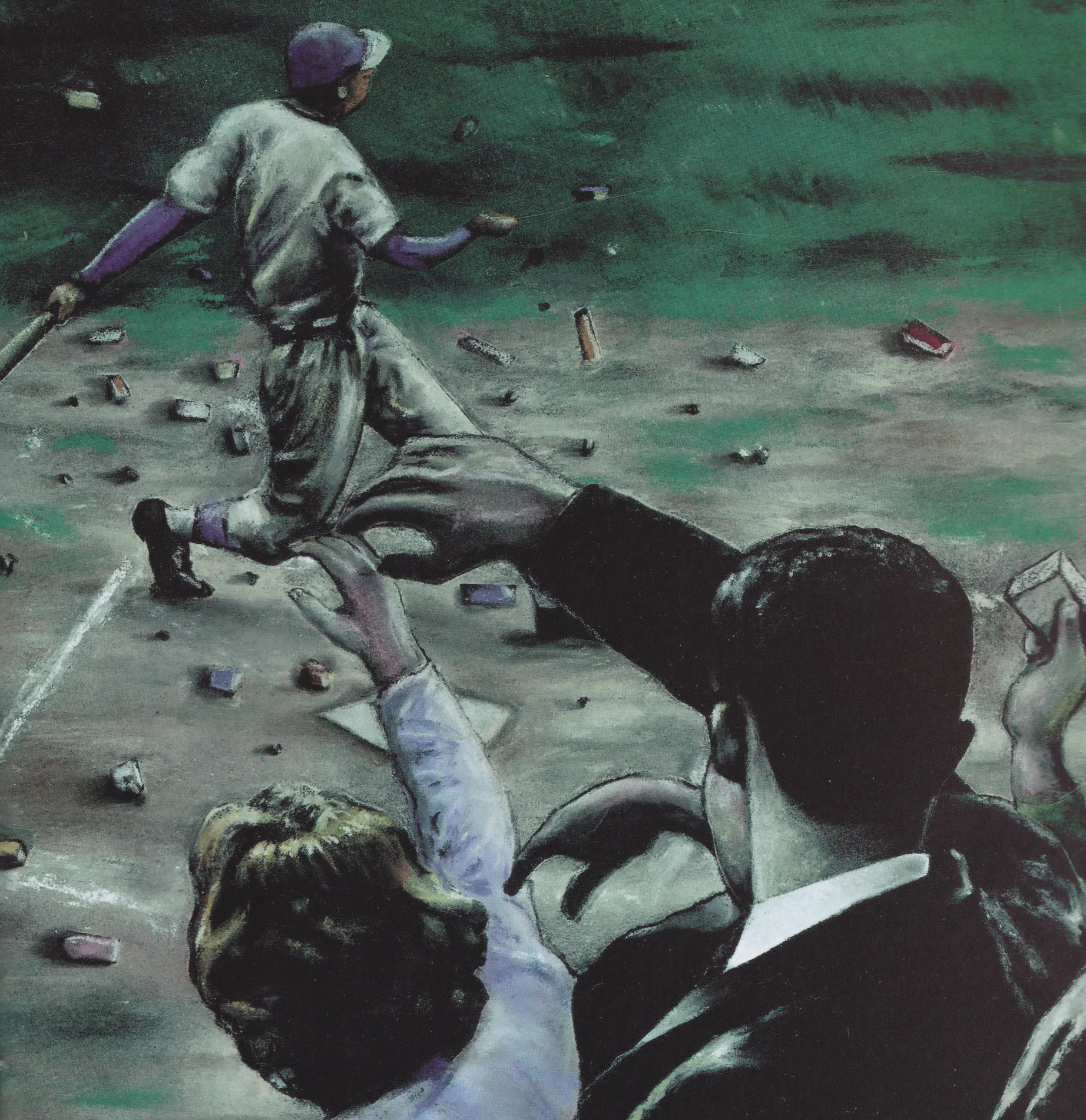

By the time the team reached the field, Gastonia was on a hair trigger. Some 2,000 were in the stands — for batting practice. Bunny was the first batter. As he dug in, hisses and boos rained down.

Bunny hit the first pitch over the left field fence. Slurs and threats flew. He sent the next pitch soaring. More shouts. He hit three more into the centerfield bleachers. Half-eaten hot dogs landed on the field. When Bunny sent the sixth pitch soaring, beer bottles thudded onto the diamond.

Manager Sid Harris pulled his team off the field. Back at the hotel, he learned that Legion teams from Florida and Maryland refused to play against Bunny. In late afternoon, Harris gathered the players.

They had a choice, Harris said. Play without Bunny — one win and on to Chicago — or go home. The team captain spoke first.

"This is a story of heroes,” writes Richard Andersen in A Home Run for Bunny. "What if Tony hadn't said ‘no’? What if he'd said, ‘Let's win it for Bunny’? Would the other players have followed him?”

But King didn’t say “let’s win it. . .” “Bunny is a member of this team,” he said. “If he doesn’t play, neither do I.” Kelly and O’Shea, Malaguti and Lombardi and all the rest agreed. Packing their bags, the team headed for the station. Their manager sent a telegram.

“SITUATION TOO DANGEROUS. STOP. BOYS THREATENED WITH VIOLENCE. STOP. BRINGING TEAM HOME.”

The team’s raucous homecoming —signs and shouts welcoming the heroes — might have ended the story. Bunny never mentioned it again, just set more records, then worked in a tire factory, putting five kids through college. He died in 1967, forgotten.

The story lingered, rarely retold. Then in 2003, a local doctor paid for a monument in Springfield’s Forest Park. Beneath a title “Brothers are We,” the story came out.

When A Home Run for Bunny was published, Andersen sent a copy to the mayor of Gastonia. John Bridgeman had grown up in Gastonia, but he had never heard the story. Bridgeman wrote a long apology to Springfield’s mayor.

In 2014, an American Legion team from Gastonia traveled to Springfield to finally play the game that was called because of bigotry. Both mayors, plus Massachusetts governor Deval Patrick, were on hand. And the first pitch was thrown out by 97-year-old Tony King, the last survivor from of a team of heroes.

The lesson remains chiseled in the monument. A team of young men — boys, really — had shown “an act of loyalty and love for their friend and brother which sent a message that bigotry has no place in the game of baseball or in the game of life."

Illustrations by Gerald Purnell from A Home Run for Bunny, Illumination Arts Publishing Company, 2013