ALAN LOMAX AND "WHERE THE SONGS LIVE"

MISSISSIPPI DELTA — 1941 — A boxy Plymouth lumbers along a dirt road in the flat, simmering cotton fields lined with workers picking. A young man hops out and shakes hands all around. With help from field workers, he drags out a machine that seems to weigh a ton. When he hands its microphone to a field hand, the bewildered man speaks into it.

“Now listen here, Mr. President, I want you to know they’re not treatin’ us right down here.”

The stranger smiles and asks if there were any musicians in those cotton fields. A broad-faced black man in overalls soon saunters forward. Sure, he plays some, he says. His name is McKinley Morganfield but folks know him as Muddy Waters. Alan Lomax starts his machine.

In a career spanning from the Depression to the digital age, Alan Lomax made 20,000 recordings. He produced concerts and festivals, hosted radio shows, wrote songbooks, and made sure a noisy planet could still hear its own music. And he did it all for a song.

“Alan scraped by the whole time, and left with no money,” said Don Fleming, director of Lomax’s Association for Culture Equity. “He did it out of the passion he had for it, and found ways to fund projects that were closest to his heart."

Lomax inherited his love of people’s songs. His father, having come by covered wagon into Texas, cherished the lonesome ballads of cowboys and ranch hands. When not teaching, John Lomax roamed the prairie, writing down chords and lyrics. In 1910, he published Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads, introducing Americans to such tunes as “The Streets of Laredo” and “Home on the Range.”

Two decades later, when Alan dropped out of Harvard, father and son hit the road. Behind them they towed the state of the art.

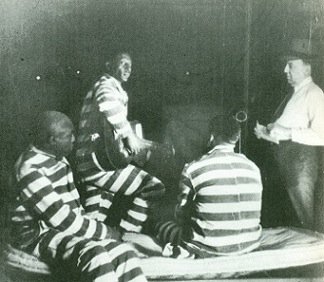

The 500-pound recording machine ran off the car’s battery. Each aluminum disc etched three minutes of music, just enough for the first recordings ever made outside a studio. After discovering a Louisiana prisoner named Huddie Ledbetter, aka Lead Belly, Alan hit the road on his own.

For the rest of the Depression, Lomax seemed to be everywhere. He was in the Delta, recording Son House. He was in Virginia recording fiddlers who seemed older than those hills. He was on the Georgia Sea Islands, led there by novelist Zora Neale Hurston. When he left the islands, he and Hurston felt “we had turned back time forty or fifty years.”

Wherever he went, folks found Lomax a curious quilt of cultures. He was a blend of Harvard and the Delta, Texas and Greenwich Village, the joy of children singing and the despair of blues on a chain gang.

“The stuff of folklore. . . can provide ten thousand bridges across which men of all nations may stride to say, ‘You are my brother.’”

Lomax worked for the Library of Congress, the Smithsonian, Carnegie Hall, the Newport Folk Festival. . . He traced technology’s rise from three-minute discs to the first tape recorders and on to digital recordings. He angered some, charmed others.

“There’s an impulsive and romantic streak in my nature that I find difficult to control when I go song hunting,” he wrote in The Land Where the Blues Began. “So, even after being snubbed, lectured, arrested, and once or twice shot at, I still persist in plunging straight for the bottom where the songs live.”

Lomax’s love of the common man colored his politics, leading to FBI investigations. J. Edgar Hoover’s boys were shocked, shocked to find in him “an erratic, artistic temperament" and a "bohemian attitude.” McCarthyism drove Lomax to England, his base while recording music from Ireland to Azerbaijan. Home again, he found Greenwich Village awash in “folk songs.”

“The idea that these nice young people, who were only just beginning to learn how to play and sing in good style, might replace the glories of the real thing, frankly horrified me. I resolved to prove them wrong." In 1959, Lomax set out on his Southern Journey, recording the music so far from any stage but so close to every heart. Age eventually ended his field work, but in the 1980s he began his “Global Jukebox.” All those songs? They’re ALL online. Listen.

The Global Jukebox allows you to sample the world’s music as Lomax did, roaming the map. CLICK — Moroccan shepherds singing their flocks home. CLICK — a Creole song with rhythmic rain sticks. CLICK — children singing in the hills of Antigua. CLICK — the world playing for Alan Lomax — and for you.

When Lomax died in 2002, he left a clutter of unfinished projects and an incredible legacy. His Southern Journey inspired the soundtrack of “O Brother, Where Art Thou,” which inspired the Roots Music Revival. Today Roots Rising on Spotify has nearly 2 million followers. The people’s music wasn’t always so revered, but Lomax and friends knew it would be — someday.

“This country's a—gettin’ to where it can't hear its own voice,” Woody Guthrie wrote Lomax when a folk radio show was canceled. “Someday the deal will change.”