HELEN KELLER'S MOMENT

TUSCUMBIA, ALABAMA — 1887 — She was “a wild, uncouth little creature.” At family meals she wandered from plate to plate grabbing handfuls of food. She cried for no reason. Threw things. Slapped strangers in the face. Her family forgave her because, after all, she could not see. Nor hear nor speak.

She lived, she recalled, “at sea in a dense fog.” And then on a March day she would forever call “my soul’s birthday,” her teacher arrived.

Anne Sullivan’s childhood was a nightmare dreamed by Dickens. Impoverished, beaten, neglected, she landed in a poorhouse where she watched her brother die. An eye disease and a series of operations left her vision faint and blurred. Her father left. Her mother died. Legally blind, she was sent to Boston’s Perkins School for the Blind where teachers found her rude and defiant. Miss Spitfire, they called her.

But teachers also saw that Anne Sullivan was brilliant. So in 1887, when Alexander Graham Bell contacted the Perkins School seeking a teacher, Sullivan was sent to rural Alabama. She got off the train that March day with little to lose.

Life seemed “primarily cruel and bitter.” And here she was, “more than a thousand miles from any human being I ever saw before. But somehow I was not sorry I had come. I felt that the future held something good for me. And the loneliness of my heart was an old acquaintance. Anyway, I had been lonely all my life. My surroundings only were to be different.”

When they met that day, the 20-year-old teacher gave the six-year-old girl a doll. Before the girl could hug it, the teacher took her hand and filled it with her own, forming strange shapes. Years later, Helen remembered being “at once interested in the finger play.” She mimicked the shapes, then groped down the stairs to show the game to her mother. “I did not know that I was spelling a word or even that words existed; I was simply making my fingers go in monkey-like imitation.”

The next two weeks were a war of wills. Tears. Screams. Broken crockery. Helen’s parents could barely stand to watch, But Sullivan showed no pity,. She kept spelling, word after word. Helen, who would forever remember seeing “the once-loved light” grow dimmer, mimicked each shape. Still, she lived in her fog.

Then one afternoon, just after Helen had smashed her doll, Sullivan trailed the wild child outside. Both followed the smell of honeysuckle to the water pump. “Water” had been one of a dozen words the precocious toddler had spoken before her illness at 19 months. Now she stood, one hand plunged in the flow, the other in Sullivan’s as she spelled. Words fail to capture what happened next, though “miracle” comes to mind.

“I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten — a thrill of returning thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that w-a-t-e-r meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. The living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, set it free!”

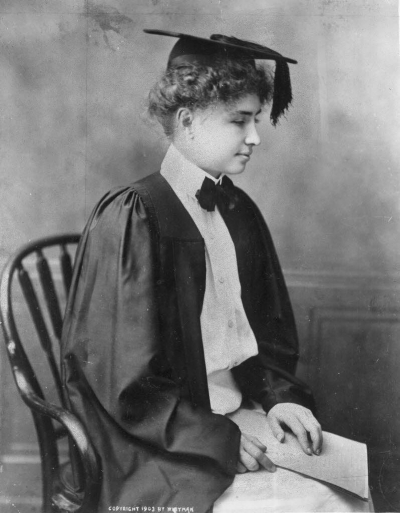

A single word unsealed the cave, opened the world. And as the world knows, Helen Keller went on to a remarkable life. With Sullivan at her side, spelling the world letter by letter, Keller graduated from Radcliffe. (Mark Twain, who gave Sullivan the name “miracle worker,” arranged her tuition.)

Keller went on to travel, speak (with an interpreter), write a dozen books, and inspire generations. Sullivan died in 1936 but Keller, with another guide, lived until 1968. To the end, every word and thought summoned “the memory of the quasi-electric touch of Teacher’s fingers upon my palm.’ And she cherished forever, that moment at the well, when suddenly. . .

“Everything had a name, and each name gave birth to a thought. As we returned to the house every object which I touched seemed to quiver with light.” She learned several words that day. Mother. Father. Brother. Sister. And the one that she would always use in addressing Anne Sullivan — “teacher.”